In this article AJR discuss What To Know When Purchasing Computer RAM

Imagine this scenario: Your trusty computer, barely a year and a half old, really hasn’t been fast as you would have liked. It’s a great system with few issues apart from its snail’s pace tendencies, but you would really like to see what you could do to speed it up. So you do a little reading.

What you find is that although there is an abundance of websites and programs promising to boost the speed of your computer, they won’t have much of an effect, if any, and may in fact just end up damaging your computer in the long run. That’s not all. Contrary to what you’ve always believed, deleting files off your hard drive won’t speed up your computer up either.

Some of what you’ve read says that you could restore your computer to a previous point in time, when everything was working correctly. Perhaps you try it. But even that doesn’t have the desired effect.![]()

Finally, you find a bit of information that suggests upgrading some of your hardware might do the trick. Although you may not know all there is to know about computers, you know enough to realize that upgrading your computer’s RAM sounds a lot simpler than replacing the hard drive. A few gigabytes of computer RAM isn’t nearly as expensive as replacing the entire computer. Relieved, you opt for that route.

But as you shop around online, you find yourself overwhelmed by the different types of computer RAM, and the terms used to describe the different products. Experience tells you that just buying something and hoping for the best probably won’t help your situation. All you want is for your computer to run smoothly. What do you do?

While RAM (random access memory) tends to be fairly easy to find and install, tracking down RAM compatible with your system can prove to be a bit more challenging than a casual user may be expecting.

Thanks to social media as well as mainstream media, information demystifying computers is much more accessible. Many casual and semi-casual users are confident enough in their knowledge that they can buy PCs and laptops with little difficulty. However, information on components still remains less mainstream, meaning that the need to upgrade hardware such as RAM can stop a casual user in their tracks.![]()

Asking for assistance from a specialist is always an option, but unfortunately it isn’t unheard of for casual users to be unknowingly scammed or sold over-priced and unnecessary products.To ensure that your system is getting the right RAM, it is up to you to research exactly what it is that you are buying. Here are 8 terms you need to know when buying RAM.

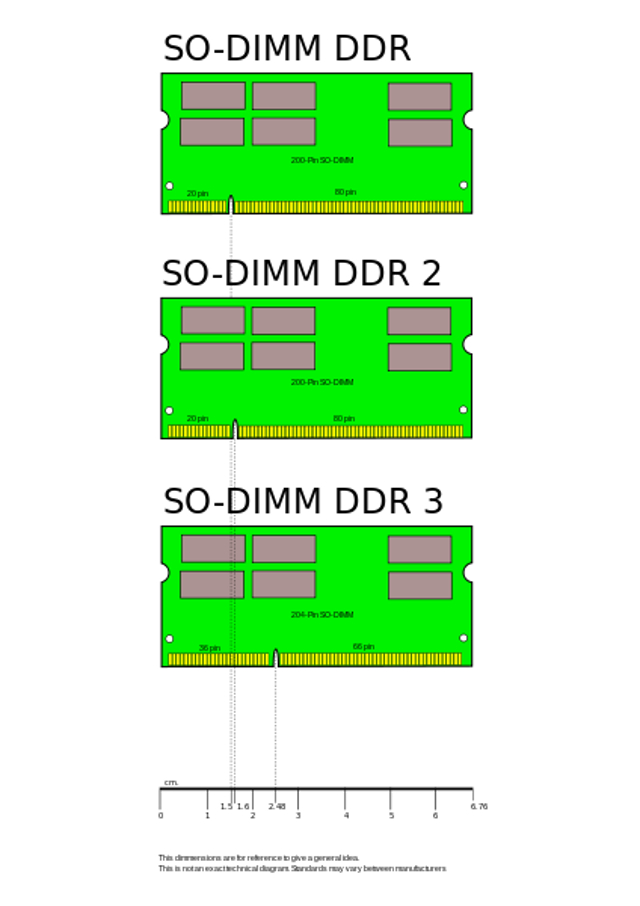

An acronym for Small Outline Dual In-line Memory Module, SO-DIMMs are considered to be much smaller alternatives for DIMMs, or Dual In-line Memory Modules. They are commonly found in systems with very limited space, such as laptops, netbooks, small-footprint PCs, or even high-end printers with upgradeable hardware.

DDR (Double Data Rate) and DDR2 SODIMMs both have 200 pins, although they are not interchangeable; fortunately, SO-DIMMs have a notch in the pins in each version to prevent modules from being installed into an incompatible system. The notch on both DDR and DDR2 SODIMMs is located at one fifth of the board length, however the notch is just slightly closer to the center of the module in DDR2. DDR3 SO-DIMMs have 204 pins, with the notch located at almost a third of the module length. Finally, both DDR4 and UniDIMM SO-DIMMS have 260 pins and are slightly larger than the first three generations.

UDIMM

UDIMM is a kind of DIMM, however the memory is unregistered, also called unbuffered. UDIMMs are most commonly used in desktops and laptop computers. Although UDIMMs are known for being faster and cheaper than registered memory, also known as RDIMMs, they are much less stable. However, RDIMMs are used often in systems where any sort of instability or error could be fatal. The slightly greater risk of a crash with UDIMMs will likely not be a serious issue with a casual or intermediate user just looking to update their personal computer.

The DDR chips in use today are a type of UDIMM.

GDDR3, 4, and 5

Graphics Double Data Rate (GDDR) is a type of memory used primarily for graphics cards. Although GDDR shares a lot of technology with the more commonly known DDR (double data rate), they are distinct from one another. GDDR3, 4, and 5 are all still in use today and can be found with very little difficulty.![]()

First used in NVIDIA’s GeForce FX 5700 Ultra in 2004, GDDR3 was developed using much of the same technological base as DDR2. However, the heat dispersal and power requirements were much lower with GDDR3. This allowed for more simplified cooling systems, as well as higher performance memory modules. GDDR3 also makes use of internal terminators, which allows this memory type to better meet certain graphics demands.

Based on DDR3 technology, GDDR4 was developed as a replacement to the outdated GDDR3. When released, GDDR4 included DBI (Data Bus iIversion) and Multi-Preamble, both of which help to reduce data transmission delay. However, GDDR4 needs to run at half the performance of GDDR3 just to achieve the same bandwidth. With GDDR4, the core voltage was reduced to 1.5 V which greatly decreased power requirements. GDDR4 modules can be rated as high as 4.0 Gbit/s per pin, or 16 Gb/s for the module.

Like GDDR4, GDDR5 uses DDR3 memory as a base. Since 2007, when the first 60 nm class 1 Gb GDDR5 memory modules were released by Hynix Semiconductor, developers have been hard at work making GDDR5 modules both larger and far more powerful. The PlayStation 4 (read our review) uses sixteen 512 MB GDDR5 chips, for a total of 8 GB. Earlier this year, Samsung announced that they had begun to mass produce GDDR5 chips rated 256 Gbit/s, in order to meet the requirements for higher resolution displays like 4K.

EDO DRAM

EDO (Extended Data Out) DRAM was designed for fast microprocessors such as the Intel Pentium. It is now obsolete. EDO RAM was intended to greatly reduce time needed when reading memory. While it was originally optimized for the 66 MHz Pentium, it is not recommended for faster computers. Instead, other types of SDRAM (Synchronous Dynamic RAM) are recommended.

When EDO RAM was first released in 1994, it brought with it a maximum clock rate of 40 MHz and peak bandwidth of 320 MB/s. Unlike other forms of DRAMs (Dynamic Random Access Memory) which could only access one block of memory at a time, EDO RAM could retrieve the next block at the same time as it returned the first one back to the CPU.

ECC and Non-ECC

ECC (Error-correcting code) memory is a special sort of computer data storage that can both identify and correct most common forms of data corruption. ECC memory chips are used primarily in computers that cannot tolerate any sort of error in any instance, such as financial or scientific computing or file servers. Usually, the memory system is unaffected by single-bit errors, and the system experiences much fewer crashes than a system incompatible with ECC memory.

Non-ECC memory, on the other hand, usually cannot detect errors in code. Occasionally, with parity support, it can. However, it is only able to detect the issue and not actually correct it. Most personal computers and laptops use non-ECC memory, which keeps the components inexpensive and accessible. Systems with non-ECC memory can also be slightly faster, as ECC memory performance can be reduced by as much as 3 percent.

Usually, ECC DIMMs have nine memory chips on the sides, which is one more than those on non-ECC DIMMs.

PCX-XXXXX

Labeling DDR DIMMs isn’t always the most effective way to express the unit’s speed. Thanks to the doubled data rate speed, a DDR DIMM rated at 100 MHz can actually perform 200 million data transfers in a second. Because of this, a 100 MHz DDR DIMM is expressed as DDR-200, a 133 Mhz DDR DIMM as DDR-266, and so on. However, bytes are a far more natural unit of measurement than the rate of transfers per second, and make calculations simpler. For that reason, DIMM speeds are assigned a PC rating.

DDR DIMM PC ratings can be calculated by multiplying the rate of transfers per second by 8, which would give DDR-200 a PC rating of PC-1600.![]()

DDR2 DIMMs, being quite a bit faster and more powerful than their predecessors, can actually reach speeds twice those of DDR. In that case, a DDR2 DIMM rated at 100 MHz could be expressed as DDR2-400, or PC-3200. Higher-end DDR2 DIMMs, reaching speeds up to 266 MHz are written as DDR2-1066, or PC2-8500. However, at this speed, using bits for the PC rating is no longer ideal. Instead, the speed is rounded down; in this case, PC2-8500’s true speed would be closer to 8,500 MB/s.

DDR3 DIMMs are even faster yet, with the most basic model run four times as fast as DDR DIMMs and are capable of 800 million transfers per second. These DIMMs can reach speeds of 6,400 MB/s and are labelled DDR3-800 and rated PC3-6400. The highest end models approved by JEDEC (Joint Electron Device Engineering Council) can speeds and ratings as high as 12,400 MB/s and PC3-12400.

Unbuffered and Fully-Buffered

RAM can be either unbuffered or fully-buffered, also known as unregistered or registered.

Buffered RAM has an extra piece of hardware that unbuffered RAM does not, called a register. The register is located between the memory and the CPU. When running, it will store or “buffer” data before it is sent off to the CPU. In systems with large amounts of memory or an extreme need for reliability, buffered RAM is used more often than not, sometimes even in conjunction with ECC RAM. Buffered RAM can also decrease the electrical usage of a system containing many, many memory modules; with more memory modules comes higher electrical usage.

Unbuffered RAM, on the other hand, does not have a register to buffer data before it is sent to the CPU. Rather than being intended for use in servers or other large systems, unbuffered RAM is perfectly capable in a personal computer.

Buffered or registered DIMMs are referred to as RDIMMs, while unregistered DIMMs are referred to as UDIMMs.

CL-X

CL, or CAS (Column Access Strobe) Latency, is a way of measuring the speed of a module by looking at the time delay between when the memory module receives a command to access a specific memory column and when the memory column is actually accessed and available. As such, the lower the CAS Latency, or CL, the better. The time interval can be counted in nanoseconds or in clock cycles, depending on if the DRAM is asynchronous or synchronous, respectively.

With synchronous DRAM today, the intervals are measured in click ticks rather than actual time, meaning the CL of an SDRAM module can vary depending on the clock cycles. For that reason, when comparing the CL of multiple modules, the CL has to be translated into real time. Otherwise, a module with a higher CL could actually be faster in real time if the clock cycle is faster.

Conclusion

With your RAM needs completely dependent on your system and how you intend to use it, knowing what your system needs to run smoothly is vital. Often times, computer RAM chips will fortunately not fit into slots in systems they are not compatible with; sometimes they do. Shoving a module not meant for your system into a slot not meant for that module can be as harmless as causing you minor annoyance, or it can also be as harmful as causing hundreds of dollars worth of damage.

Sometimes our computers are slow for reasons other than RAM. With so many of us lacking the funds necessary to replace a computer without warning, purchasing the incorrect hardware for our computers simply isn’t an option.

Instead, before buying RAM, take a look at your computer and the memory chip manufacturers approved for your computer. Be sure you know what you have, and also know what you need. As Uncle Ben said, with great power comes great responsibility. You have the power to upgrade your system as you please, but you also have a responsibility to know what an upgrade requires.